How to Call in Sick to Work What to Say

Why do ill people still come in to work?

(Image credit:

Getty Images

)

Coming to work while sick can take out a workforce. So here's how to tell your boss you need time off to recover.

T

The number of sick days taken by UK workers has almost halved since 1993, according to the Office for National Statistics. Where the average employee once spent 7.2 days a year at home due to illness, they took just 4.1 days off in 2017.

It's difficult to attribute the change to general advancements in medicine, says Kylie Ainslie, a research associate in the Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at Imperial College London; people aren't necessarily getting sick less often.

Instead, experts say a shifting work culture is to blame for creating a stigma around taking time off. Studies show that mistrust and fear of judgment from bosses have forced an increasing number of employees to come to work when sick.

The flu season - which peaks between December and February in the northern hemisphere - is when absences spike. It's the time of year when the air is coldest and driest, the ideal conditions for the influenza virus to transmit quickly. Medical professionals agree that staying at home during the early stages of the flu – the first two days after catching the virus when the risk of contagion is at its highest – is essential for the health of both the affected workers and their colleagues.

But according to a 2015 survey from UK insurance provider AXA PPP, nearly 40% of employees don't tell their manager the real reason for their absence when calling in sick because they're afraid of being judged or disbelieved.

During flu season, it's imperative that sufferers stay at home while they're still contagious (Credit: Getty Images)

For unlucky people whose employers pressure them not to skip work, knowing how to effectively communicate the need for time off is a crucial step towards preserving both their own health and productivity, and that of coworkers.

Sickness stigma

So why do some bosses give sickness short shrift?

As new technologies and instant connectivity have infiltrated global businesses, a new work dynamic has emerged. Depending on the industry, being present in the office is no longer a requisite for being productive. Many workers are equipped with all the necessary tools – a computer and wifi – to function away from the office.

But with the freedom to work anywhere has come a wave of mistrust from managers who can't monitor their subordinates in person.

George Boué, vice president of human resources at commercial real estate firm Stiles Corporation, says the stigma comes from "older generations that never accepted that someone can truly be working productively from home". It manifests as a form of resistance to the concept of a decentralised workplace in which employees are trusted to keep themselves on task.

The combination of distrust and the constant quest for maximum productivity has led some managers to view sickness-related absence with a similarly critical eye.

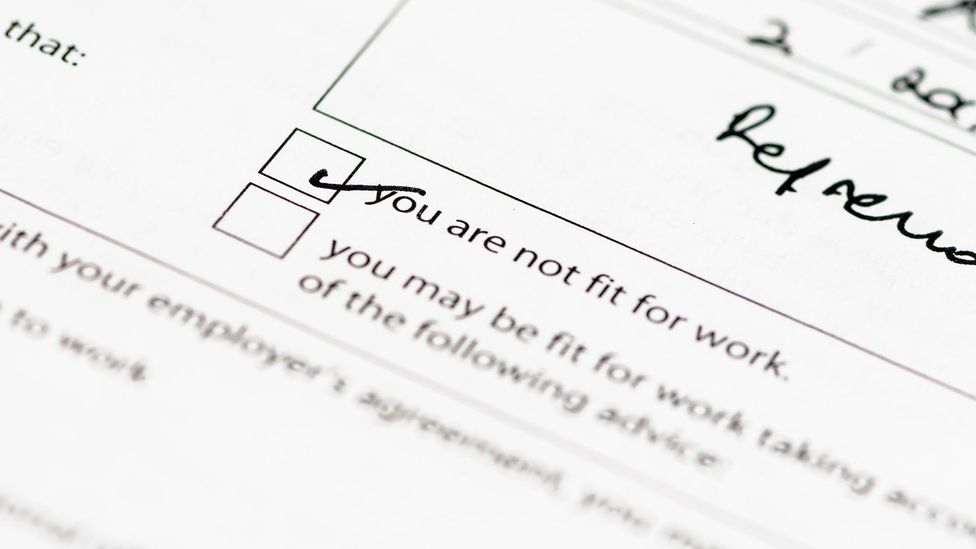

A statement of fitness to work, or "sick line" - more employers are sceptical of employees who stay at home whilst ill (Credit: Alamy Stock Photo)

Only 42% of senior managers polled by AXA PPP agreed that the flu was a serious enough reason for absence, with less than 40% saying the same for back pain or elective surgery. The study further found that employees were much more likely to lie to their boss about the reason for staying home if the cause was related to mental health (39% would tell the truth) rather than physical health (77%).

But it's not just management attitudes that force us into work when ill. Many of the jobs that were once formal and full-time have become fitful and fleeting in the gig economy.

Today, as Pete Robertson, associate professor at Edinburgh Napier University, wrote in 2017: "Work can be temporary, fixed-term, seasonal, project-based, part-time, on a zero-hours contract, casual, agency, freelance, peripheral, contingent, external, non-standard, atypical, platform-based, outsourced, sub-contracted, informal, undeclared, insecure, marginal or precarious."

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, both the number of job openings and job separations have seen an increase in the last two years. As the turnover rate continues to climb, it's no wonder workers are holding tighter to jobs – even if they have to show up sick.

This practice is referred to as 'presenteeism': people coming into work when they are ill.

A woman receiving her seasonal flu vaccination at a pharmacy in 2017 (Credit: Getty Images)

The problem with presenteeism

Presenteeism has more than tripled over the last decade, according to the Chartered Institute of Personnel Development. Of over 1,000 participants in its 2018 study, 86% claimed to have witnessed instances of presenteeism in their organisation during the previous year, up from just 26% in 2010.

"With managers showing so little understanding of or support for employees suffering from illness, it's not difficult to see why employees worry about phoning in sick," Glen Parkinson, small-and-medium-sized enterprise director for AXA PPP, wrote in 2015. "Employers need to trust employees to take the appropriate time off sick and, where practicable, consider allowing them to work from home."

Allowing presenteeism could be much more costly for a company than creating an environment where people feel able to take sick leave; contagious employees have a knock-on effect. And when it comes to mental health or other illnesses, allowing people to take the time they need early on may mean less recovery time later.

Spending a day at the office while sick could cause an increase in workplace flu cases by as much as 40%, according to a 2013 study by the University of Pittsburgh. Researchers used population data from more than 500,000 employees in an epidemic simulation in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, to calculate the hypothetical spread of the influenza virus. The results showed that 66,000 infections – 11.5% of the total number of employees – were caused through workplace transmission.

The study's most telling scenario implemented a "one or two flu day" stay-at-home policy, resulting in nearly 17,000 fewer infections for a one-day policy (about a 25% drop) and 26,000 fewer cases for a two-day policy (a nearly 40% drop).

Breaking away from the practice of presenteeism has clear benefits to the long-term health of the workplace. In jobs that lack a formal policy, however, it's up to employees to communicate their needs to managers in a way that doesn't impede daily operations.

A policy of honesty

Experts say the earlier an employee can notify their manager, the better. Establishing a line of communication with a boss at the onset of sickness can both convey respect and allow them more time to plan around the absence. Above all, being honest is the best way to avoid misunderstanding or resentment.

"The right way is to follow policies and procedures of the organisation," says Mark Marsen, director of human resources at Pittsburgh-based health services company Allies for Health + Wellbeing, and a member of the Society for Human Resource Management's HR discipline expertise panel. "The absolute wrong way is to lie or exaggerate."

Marsen says there are two types of managers. The first believes that employees are inherently not willing to work and thus need a lot of rules. These managers will be predisposed to think the worst of any employee, especially when illness is brought up as an excuse for being out of the office.

The other kind of manager will try to set reasonable standards and trust employees to be adults. The onus is on managers themselves to create a culture where employees feel empowered to take time off, he says. The best way is through leading by example.

"This means staying home and truly offline when you're feeling too sick to work, so that your team knows it's okay to do the same when they aren't feeling well. It's also important to avoid contacting employees who are at home sick unless it's for something truly urgent."

Finding the balance will always be a two-way street, requiring both employees and bosses to consider the responsibilities and wellbeing of the other before adding pressure. Especially during the flu season, it's crucial to reduce instances of presenteeism.

"A good boss should empathetic and understand," Boué says. "Nothing builds a greater bond between boss and subordinate than showing genuine caring."

--

To comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Capital, please head over to ourFacebook page or message us on Twitter .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com featuresnewsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

How to Call in Sick to Work What to Say

Source: https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20190227-how-to-tell-your-boss-youre-sick-and-why-you-should