Soul of a Nation Art in the Age of Black Power

Barkley Hendricks (American, 1945–2017). Blood (Donald Formey), 1975. Oil and acrylic on sail, 72 x 501/ii in. (182.9 x 128.3 cm). Courtesy of Dr. Kenneth Montague | The Wedge Collection, Toronto. © Estate of Barkley 50. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist'south estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum)

William T. Williams (American, born 1942). Trane, 1969. Acrylic on canvas, 108 x 84 in. (274.3 ten 213.4 cm). The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York. © William T. Williams. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

William T. Williams began making "difficult-edge" abstruse paintings at Yale, where he studied with artist Al Held. This painting was named afterward jazz saxophonist John Coltrane and may conjure the cascades of sound in his performances.

Trane was made in New York in the same year that Williams—as a member of the Smokehouse Associates—created a number of abstruse wall paintings in Harlem. That yr he also set the artist-in-residence plan at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Carolyn Lawrence (American, born 1940). Black Children Keep Your Spirits Free, 1972. Acrylic on canvas, 481/two x 50one/2 x vone/four in. (123 x 128 x 13.v cm). Courtesy of the artist. © Carolyn Mims Lawrence. (Photo: Michael Tropea)

Faith Ringgold (American, built-in 1930). U.s. of Attica, 1972. Beginning lithograph on paper, 213/4 ten 27ane/2 in. (55.2 x 69.9 cm). © 2018 Courtesy ACA Galleries, New York. © 2018 Faith Ringgold, fellow member Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Here, Religion Ringgold documented the 1971 uprising at Attica Prison, over demands for inmate rights, that left forty-three dead. The image presents the Attica Prison riot not as an isolated event but as an American tragedy to be understood inside an ongoing, nationwide context. The caption reads: "This map of American violence is incomplete / Delight write in whatsoever y'all discover lacking."

At the tiptop of its popularity, this impress was circulated as two 1000 small-format posters. Ringgold first studied printmaking at the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School founded by Amiri Baraka.

Roy DeCarava (American, 1919–2009). Couple Walking, 1979. Gelatin silverish print on paper, 11 x 14 in. (27.9 x 35.6 cm). Courtesy of Sherry Tuner DeCarava and the DeCarava Archives. © 2017 Estate of Roy DeCarava. All Rights Reserved

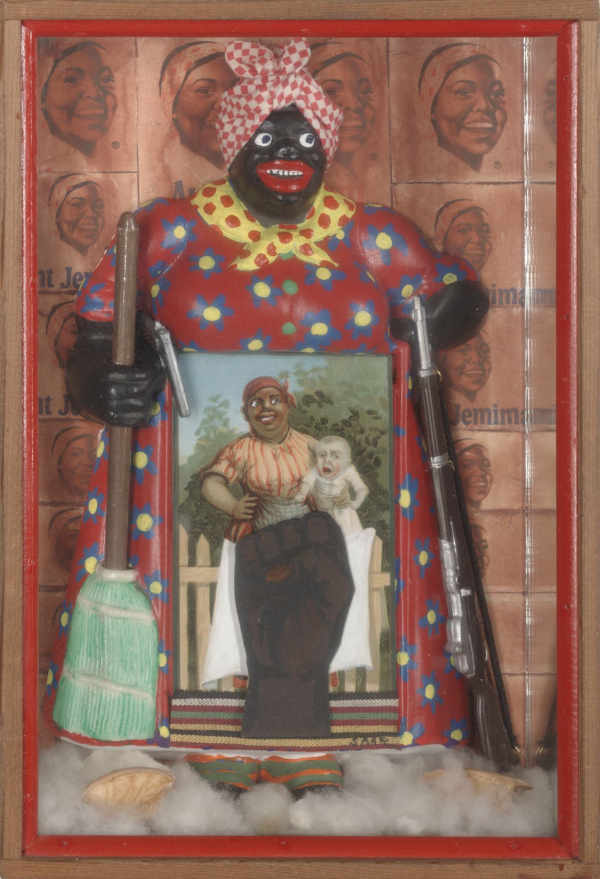

Betye Saar (American, built-in 1926). The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972. Wood, cotton fiber, plastic, metallic, acrylic, printed newspaper and textile, eleven3/iv x 8 x 23/iv in. (29.8 10 20.three x 7 cm). © Betye Saar. Collection of Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, California; purchased with the aid of funds from the National Endowment for the Arts (selected by The Committee for the Acquisition of Afro-American Art). © Betye Saar. (Photo: Benjamin Blackwell. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles)

Perhaps Betye Saar'due south best-known piece of work, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima juxtaposes radical Black Nationalist imagery of weapons, a raised fist, and African kente textile with Aunt Jemima, the Southern "mammy" recognized equally the face of the best-selling pancake mix and a stereotype of grin, docile servitude. Saar was appalled by racist depictions she found on everyday objects at flea markets and in curio shops. Inspired in part by Joseph Cornell's Surrealist assemblages, here she incorporated a kitchen notepad holder in the form of a Black female person figure. Moved past the strength and determination of Black women, Saar sought to recast a painfully enduring image of Blackness female subservience as a symbol of empowerment.

Alma Thomas (American, 1891–1978). Mars Grit, 1972. Acrylic on sheet, 69one/four x 571/8 in. (175.9 x 145.i cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from The Hament Corporation, 72.58. © Estate of Alma W. Thomas. (Digital image: © Whitney Museum, N.Y.)

Mars Dust was one of a serial of paintings that Alma Thomas included in a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1972. At age 80, she became the commencement African American woman to have a solo prove there. Fascinated past the technological advances of the infinite historic period, she looked at daily reports of NASA'southward Mariner 9 mission to photograph Mars. Huge dust storms on the planet, which initially prevented the relay of images back to Globe, inspired her to make this work.

Frank Bowling (American, born 1936). Dan Johnson's Surprise, 1969. Acrylic on canvas, 116 10 1041/eight in. (294.v 10 264.5 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Friends of the Whitney Museum of American Fine art, seventy.fourteen. © Frank Bowling. Image courtesy of the creative person and Hales Gallery. (Digital image: © Whitney Museum, North.Y.)

In the late 1960s and early on 1970s, Frank Bowling's work drew from Color Field painting of the 1940s and 1950s, yet maintained representational images. He poured waves of acrylic over stencils of continents, which were removed before more than paint was applied, leaving ghostly outlines. Continents emerge from and disappear into color; oceans and rivers are combined with pools and trails of liquid paint. While many Black Americans were pointing to Africa as a female parent continent, Bowling's maps celebrate a more fluid and open thought of identity and belonging in the earth, enacting what scholar Kobena Mercer calls a "decolonial space of decentering." Texas Louise and Dan Johnson's Surprise were included in Bowling's solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in tardily 1971.

Born in Bartica, Guyana, Bowling moved to England in his teens. In 1966 he relocated to New York, where he joined a group of abstract artists and included many of them (such as William T. Willliams and Daniel LeRue Johnson) in his 1969 exhibition 5+1 at the Land University of New York at Stony Brook. This exhibition, and Bowling's extensive writings, argued for an expansive notion of Blackness art encompassing both abstract and figurative.

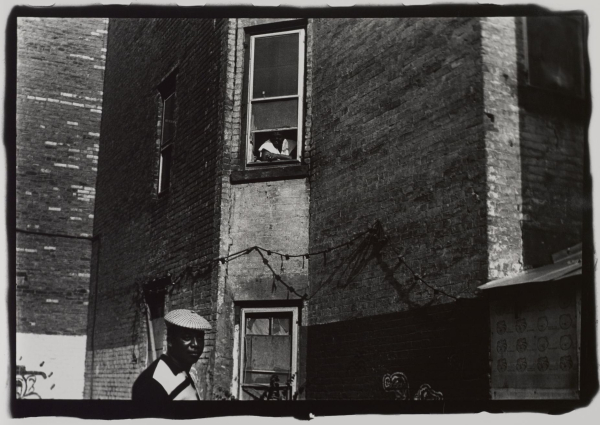

Ming Smith (American). When Y'all Encounter Me Comin' Heighten Your Window High, 1972. Vintage gelatin silver print, 11 x fourteen in. (27.nine x 35.half dozen cm). Courtesy of the creative person and Steven Kasher Gallery. © Ming Smith

Source: https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/soul_of_a_nation